"Tony": this book covers the life of Ernest Frederick Wilton Schiff, Sydney Schiff's younger brother, from his childhood in the 1870s and up to and including his death in 1919.

Here should be the fictional family tree: it will be eventually.

The Fictional Kurt family |

Stephen Klaidman, ‘Sydney and Violet’, 2013.

Sydney Schiff used his earlier books 'Prince Hempseed', 'The Other Side', Elinor Colehouse', 'Richard Kurt' and 'Richard' Myrtle and I' to create his autobiographical saga 'A True Story'. However, his other book, 'Tony', could not fit into this sequence because, unlike the other books that are written from the same viewpoint, that of the author, Sydney Schiff chose to write the account of his brother's life with the voice of his late brother in the first person. As this account ends with 'Tony's sudden death, this does cause some awkwardness: it is as though the nover was written autobiographically but posthumously.

The book is very interesting though as a biography of a very interesting personality. He was undoubtedly a scandalous rogue: expelled from Eton (or whichever public school he did actually attend), a notorious womaniser - in addition to his long-term mistress Seline Moxon ('Trixie' in the novel) he had many other liaisons, including the internationally famous French courtesan Liane de Pougy. (By a curious coincidence I first came across her as a child: her photograph had been cut out of a magazine in about 1910 by my English great grandfather.)

I have deliberately transcribed sections of the book which seem obviously biographical, and have attempted, where possible, to supplement the account with quotations from contemporary newspapers and archives. So far everything does indeed seem to be true, it really is only names and places that have had their identities changed.

Frank Gent

Tony

p. 6: Childhood Pranks

You ought to have told about my being at St. Vincent’s, you ought to have explained how much we loved each other but that we always quarrelled, mostly because of your jealousy… And you ought to have told how you bullied me—and then were sorry and kissed me—and of how I always thought you were right when we were small… You ought at least to have mentioned my having shared those beastly tutors with you, and about our locking that awful one Whyte into the stable at Craythorne and about our watering the roses with manure-water because the governor wouldn’t let us make a cricket pitch on the lawn; that was my idea. You ought to have brought me in at Heidelberg, when I threw my knapsack out of the train window and queered the governor’s rotten scheme for a walking tour. How we both loathed walking! And how could you help mentioning that it was after our talking it over the whole last night of the holidays that you made up your mind to bolt on your way back to Clive and that when you went off to America, I got the chuck at Eton and they sent me to old Reinhardt at Bonn.

p.8: Hamburg

We hardly ever wrote to each other, I only remember one decent letter from America after the Sullivan-Kilrain fight and I wrote you a long one about Frida just before I left Hamburg. In that letter I gave you an account of the row I got into with Uncle Fred while he was on a visit to the aunts through my bringing a girl into old Jacob’s study…

[ The fight is referred to in Stephen Hudson's autobiographical novel 'The Other Side'. Here is an account of the fight which took place on 8th July, 1889:

http://blog.syracuse.com/sports/2012/06/end_of_a_boxing_era_the_tale_o.htmlHere are some images of the fight:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W8_8lM8IhIw

Henriette Lazarus's husband was Dr Jacob Lazarus of Hamburg; he died in 1881.]

p. 10: Elinor’s Arrival

I wasn’t nineteen then…

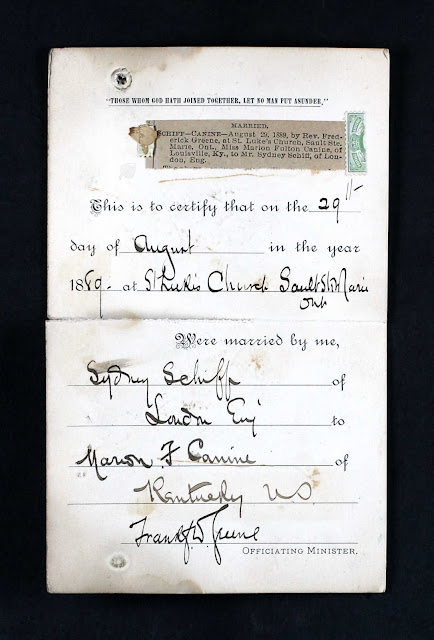

[Ernest Frederick Wilton Schiff ('Tony') was born in 1870, thus corroborating the chronology: Sydney's marriage to Marion Canine Fulton took place in 1889.]

p. 12

By the time I got there you were all having tea. Helen and George Hayes were there and Ada and Olivia. Percy Macfarlane and the two Bulmers had turned up with the girls…

[The sisters were Carrie born 1865, Edith born 1871, Rose born 1874 and Marie born 1877. Carrie, here called Helen, married Sidney Alexander towards the end of 1890.]

p. 14

Afterwards you said mother had told you about Helen’s engagement…

p. 15

She knew mother had lovers as soon as she set eyes on her and that the governor was an old rip.

p. 16

It was then I pulled out the letter the governor wrote after he got the cable which came from that American doctor announcing your marriage.

p. 17

I’d been talking to her about Ada’s affair with Percy and Olivia’s with Hugh Bulmer… I was nineteen and you were twenty-two and married over a year.

p.18

What if I had ben sacked from Eton, so were Fitzroy and heaps of other chaps, some of the very best, even some of the cleverest for that matter. And the slip-up at Bonn didn’t weigh on me either. As for the Hamburg row, all I felt was that Uncle Fred had no business to poke his nose into my affairs. What business was it of his if I had pleasant company down below there on the ground floor. Dear old Emma wouldn’t have minded my keeping her husband’s ghost warm; in fact I nearly told her before Uncle Fred came.

[Emma was his father's sister, Henriette Lazarus.]

p.19

All the same, I decided for it and tackled the governor the next morning when he was writing his usual Sunday letter to the aunts.

The three sisters lived together in Hanburg: Henriette Lazarus, Jenny and Virginia.]

p. 20

I could speak German about as well as English…

p.22 While the preparations for Helen’s wedding were going on in London, the roof fell in at Copenhagen and back I came. I must say the governor behaved very well over that; whatever their faults were, he and Uncle Fred knew something about women.

[This must have een the summer of 1890.]

p. 25

She sneered at all of us going to the station to see mother off, the arrival at the station in the brougham, the reserved carriage, John and her maid, flowers, the governor, Uncle Fred and Benda escorting her as far as Cannon Street, the old ceremony.

p. 26

Amongst the people who filled up Ennismore Gardens for Helen’s wedding was old Nanny… One evening Nanny suddenly said “I wonder what the master will do about Miss Helen at the register.”

I pricked up my ears. “What d’you mean, Nanny?” I asked.

At first she wouldn’t explain but after a time, and after making me swear I’d never give her away, she told me that Helen was born before mother married the governor and wasn’t his daughter. She said said she didn’t know who her father was...

[This refers to the unknown parentage of Carrie. At the time of her birth her mother, Caroline Scates, was still married to John Scott Cavell, but allegedly neither he nor Alfred Schiff were her father, though I suspect he was.]

P.30

About eighteen months later you were in a flat in Hanover Square...

Meanwhile also, mother was moving the family establishment into Mayfair where the governor had been running another, under the rose, for some time.

P. 31

I must say that was an uncommonly cosy flat of yours. I turned up there unannounced one foggy November afternoon and found Elinor with that pretty little witch, Gerty, who had chucked Musical Comedy and was playing it up as Lady John Dunglass. She was fearfully excited about my affair with Liane de Pougy, the trouble was I couldn't keep that simmering without money and where was that to come from?

[I had thought that the affair with Liane de Pougy was that referred to in 'Tony''s bankruptcy, but that wasn't till much later, in 1910. Liane de Pougy was born in La Fleche in 1869. 'Tony' must have had his affair with her in about 1891-2, when she was a dancer at the Folies Bergeres.]

P. 32

While I'd been away, Elinor had made friends with Maggie, the sort of thing women call friendship. The very next day, off she went to her and gave the whole show away without saying a word to me. She got nothing out of Maggie, but our charming cousin promptly blew on her to mother. You know the rest.

p. 33

Mother wasn't soft like you; she knew the sort of woman she had to deal with and the terms were what you know. You were down and out and in the wilderness until the day of her death.

p. 36

A short time after that you went to Biarritz and I came my first real big mucker. I don't remember how much it cost the governor that time, but the best terms I could make included my beating it to Australia.

[In fact 'Tony' went not to Australia, but to New Zealand. Passenger List records show that he arrived there in the autumn of 1893.]

p. 40

When I came back from Australia with Nancy and the boy you were in the thick of it at Lyncroft.

[He married Esme Clementine Borlase in New Zealand in 1897.]

p. 44

I told you how I met Nancy and made up my mind to marry her and partly because I saw it was the only to make good with the governor after all that had happened.

...she bored my soul out of me, and if you'd ever been in Australia, you'd know that no woman from there could ever be anything but middle-class and provincial. the so-called gentry have got the country parson type of mind and Nancy had the stereotyped, puritanical, hypocritical notions of a nicely brought up vicar's daughter.

[1897/4205: Emma Clementine Borlase and Ernest Frederick Wilton Schiff]

p. 48

He and Uncle Fred had forked out to start you as a sort of country gentleman and me as a stock-jobber, both of us had pretty handsome allowances. Ada was running the establishments in London and the South pretty much as she liked and Olivia was to get a substantial settlement when she married.

p. 60

It was at that dinner that I introduced you to Marguérite. Elinor had persuaded you to take the house in Wilton Place.

p. 62

That was the beginning of your long affair with Marguérite…

p. 67

The boy was getting big and strong and Edie was nearly two, I think, when the governor invited us all to the villa to spend a few weeks of the winter. I was doing pretty well on the Stock Exchange but of course I was spending twice as much as I made…

['Tony''s daughter Esmé was born in 1900, in London.]

p. 72

The next thing that happened, as far as I can remember, was the Boer War. Another change came over you. You began by making yourself unpleasant to everybody by sympathising with the Boers, going on just as you did at the time of the Wilde case.

p. 79

I’d heard nothing of or from you for months when one morning just as I was leaving for the City, old Uncle Theo rang me up on the telephone and told me you were down with typhoid at Alfredo’s place in Italy and he intended going out there to see you that very day… The governor, he said, didn’t take it so seriously… But I decided then and there to go with Theo and told him I’d meet him at Charing Cross for the night boat. Meanwhile off I put to the City and went straight to W. K. & Co.’s office where Uncle Fred was in no end of a state about you… that night the three of us went off to Coneglio.

['Uncle Theo' was Charles Schiff, also known as Carl Gottlieb and Teofilo.]

p. 80

The Contessa had prepared a sumptuous breakfast and she, her daughter Zoë, Alfredo and Elinor were waiting for us...

The Contessa had prepared a sumptuous breakfast and she, her daughter Zoë, Alfredo and Elinor were waiting for us...

...The Contessa was very handsome; she had a mass of snow-white hair and the kind of sallow skin that looks like yellow ivory. The governor, who, like me, can throw things off, sat on one side of her making himself agreeable and talking about friends they had in common at Trieste where she came from; his reddy grey beard showed up against her black velvet dress and he looked as spick-and-span as though he’d just dressed, although we’d had to sit up in the train for two nights. Uncle Theo sat on the other side of her, looking tousled and tired, the top of his bald head, which he was leaning upon his hand, caught the shine of the candle-light.

p. 92

After we’d been back about ten days, the governor dined with Nancy and me one night and after dinner he said he had something to say to me. I wondered what was up, more or less taking it for granted that there was some trouble brewing with my firm. But it was something very different. The old aunts had, of course, been informed by their brothers of your illness and the poor old things had been very perturbed. They were going to Italy for the winter anyhow but they had hastened their departure to go and see how you were getting on.

p. 95

When one comes to think of it, the governor was very easy really, one could always play upon one or the other of his weaknesses or fads or prejudices. Uncle Fred was always a harder nut, especially when he got wise and I tried him a bit too high at the last.

p. 97

I didn’t tell you that Marguérite had sent her love to you and would be glad to know when you were going tolet her have her half-year’s rent and I didn’t inform you that the call option on Bloemfontein Estates which my firm had bought for you had resulted in a five points profit…

p. 104

About the time I went to see you at Florence, I was by way of working a new partnership deal with Sammy Michaelis. Sammy was all right, he was a pal, and he knew my position. He wanted capital and was on the right side of the old man with whom I always believed he had a pull because of something he’d done for him behind the curtain.

p. 107

You spotted old Theo as being at the bottom of it and he was, in a way, through Elinor’s writing Aunt Kate that you and the Yank girl were living in sin together. You didn’t take that at all in a saintly fashion. On the contrary, you wrote the old chap a stinker, telling him he was suffering from senility, which, as it was jolly near true, hurt his feelings deeply...

p. 117

I was completely flabbergasted when, as I went along the train at Charing Cross to find the governor’s carriage, I caught sight of you standing on the platform. Uncle Fred was too anxious about the old man to think about anyone else, but Leslie, jostling him along with me through the crowd, kept on asking me breathlessly what you’d come for, as though I knew any more than he did.

It was plain to see that the old man was done for, he had to be almost lifted out and if the car hadn’t happened to get close up, I don’t know how we should have got him into it. On the way to Brook Street you told me you’d come on with him because you thought he might die on the road. That would have sounded all right to anyone else but it didn’t convince me if only because all the baggage you had was a handbag and I knew you too well to believe you’d have left without a change of clothes. But it wasn’t only that. I could see your nerves were on edge and that you didn’t know what to say, in fact, you didn’t know where you were. I knew something had happened but there were no twos to put together; I couldn’t get anything out of you.

That was an awful evening at Brook Street. The governor insisted on sitting through dinner and the rest of us had to pretend to carry on as usual. Leslie came in useful, for once, talking about Ascot, It wasn’t until afterwards, when we got the old man into the arm-chair in the library, that we were able to take a pull on ourselves with the help of the old brandy.

You didn’t make much of a job fobbing off Olivia’s questions about how you’d left Elinor and how long you intended staying. You said you’d wait and see how the governor went on but even she saw that you were dodging and, before they went away, Leslie followed me into a corner and began cross-questioning me in that riling way of his. What did I think had happened, etcetera? You looked relieved when they said good night. When Uncle Fred came out of the library with you and told me to go in to the governor, I knew they’d been talking about you and that something was up.

The old man was wonderfully cheery when I went in, said it hadn’t been at all a bad journey and he’d been very glad of your company. It was awful talking to him, he couldn’t utter a word without coughing himself to pieces, and I must say he was tremendously plucky. He asked me how the boy was getting on at school and said he hoped Nancy would bring Edie to see him the next day but he didn’t say anything more about you and presently he asked me to help him sit down at his writing-table. He took a sheet of paper, I knew he was going to write to the aunts and that the first words would be “Meine liebsten.”

Uncle Fred and you didn’t talk long. When you both came back into the library he stood with his legs apart in front of the fireplace as he always did, pulling at his cigar and looking at the ground; we none of us said a word and the governor went on writing and coughing, crumpled up over the table; a ghastly business. You nodded your head at the door and we went into that dreary hall and sat down on two of those comfortless leather chairs; we couldn’t even have a drink because the tray was in the library. Then you suddenly said “I’ve left Elinor for good, they both know it” and dried up with a look on your face as though you’d put on the black cap and were sentencing some poor devil to be hanged…

…No, you had not yet told Elinor you intended leaving her, you were going to write her that night before you went to bed and you wished you had someone to send with the letter and bring you back your clothes. I told you I could lend you Ruggles and you were very much obliged. The next morning he went off with the letter. The morning after, the old man had a haemorrhage and it was all over.

The less said about the next three days the better. I don’t pretend, personally, to have felt it all very deeply. Any sentiment I ever had for the governor had been worn out years before and my mind was almost entirely occupied with speculating as to how much he’d left and in what way he’d left it. I didn’t agree with you when you said it would all be tied up. But you didn’t seem to care one way or the other. You behaved much the same as when mother died, going about with your silk hat brushed the wrong way and looking as if it were your own funeral you were seeing about. I couldn’t understand why you cared so much just at the end considering you and the governor never hit it off. There were moments when he and I understood each other because we were of the same kind in one way, the canaille side of him I mean. But there never was anything of that in you and your both having fussy, meticulous habits couldn’t have brought you much together.

[Schiff, Alfred George aged 68. Chertsey, Surrey 2a 35]

[SCHIFF Alfred George of the Stock Exchange and Warnford Court Throgmorton-street London died 2 August 1908 at Brooklands Weybridge Surrey Probate London 28 October to Ernest Frederick Schiff stockbroker and Basil Henry Williamson solicitor. Effects L576769 4s. 2d.]

[...Alfred George Schiff, of the London Stock Exchange and of Warnford-court, Throgmorton-street, London, Stockbroker, deceased, who died on the 2nd August, 1908, and Brooklands, Weybridge, Surrey...]

p. 122

After the coffin had been lowered into the grave, Uncle Fred stood looking down into it as though he had half a mind to jump in himself.

[According to his will, Alfred requested cremation.]

[According to his will, Alfred requested cremation.]

p. 128

At that time I used to go and see Uncle Fred every morning at the office, partly to ask him if he had any business for my firm but much more because it was important for me to keep on the right side of him. Uncle Fred had become very important to me and what was more he was becoming very important to a good many other people. Since the governor’s death he had taken hold of the business and was running it for all it was worth, and in quite a different way, by cutting down the commission part of it and going in for underwriting and financing on a large scale. He had come to this through realizing the governor’s estate which left him with what he called “the rubbish.” This “rubbish” was the speculative shares which had meanwhile gone up so much that they were worth about half a million more than when the old man died. It was so like Uncle Fred, quietly to sneak that surplus by pretending it wasn’t good enough to keep for the family trust. There’s more to be said about that, a trifle of hundred thousand pounds.

When I went up to see him he was either reading the "Times" or looking over the letters and telegrams. He sat in the same chair he'd always sat in, no one ever occupied the empty one on the opposite side of the big double writing-table. The only change was a photograph of the governor in an ebony and silver frame beside the inkstand. He never looked up when I came in. When I said good morning, he'd grunt and go on reading. I'd sit down, not in the governor's chair, and wait, twiddling my thumbs and smoking a cigarette till he said "What are so and so?" and when I told him "Buy or sell so many at such a price" or "Keep me informed." Just as I was going out of the door he'd ask if Nancy and the children were all right and very often "Heard anything of Richard?" When I said I hadn't; "I don't know what he's doing, he came to see me on Sunday mornings for a time when it suited him but he never told me anything then and I haven't seen him for a month. What's he doing, eh?" And he'd look at me over his glasses. I'd say, "I haven't the least idea." Another grunt. That meant "You're lying. You know, but you won't tell me."

p. 130

At the beginning he seemed to be not exactly broken, but much older, he hardly said a word to anyone. The people at the office especially Kahn and Bellows, were in an awful funk, they were certain he would liquidate the firm. He took no interest in anything. That only lasted a few weeks, the next stage began with the settling up of the estate. As it went on, he hardened up and as markets improved and stocks rose, he got harder. He didn't talk any more or look any more cheerful but he got keener and keener, came earlier and went later. Kahn and Bellows bucked up; secretive as they tried to be, they admitted that they were doing a big business Old Baron d'Alger [d'Erlinger] was dead and his son, who was head of the firm, was always sitting in the old man's private office brewing up financial schemes. The name of W. K. & Co. was on most of the important prospectuses of new companies and there were comings and goings to Rothschilds, Morgans, Cassel, Speyers and all the big houses. It didn't take me long to see that Uncle Fred was out for the stuff as he'd never been before. He'd made up his mind to run the show in his own way and now he was alone, he could do it.

p. 131

There's another point I must put in here, that is that Uncle Fred cared more about you than about anyone else; he always had, just as you'd always cared about him. What you could find to be fond of in him, I never could understand. The governor did have a good side, at least he liked enjoying himself, gambling, tarts and other things that are human.

p. 134

What concerned me was you were apparently quite unaware that you were horribly ill.

p. 136

I knew you'd had some training under Uncle Theo as a boy and that short innings of yours with W. K. & Co., but that was quite a different sort of thing to this company-promoting stunt you were so at home with.

p. 137

The only person who might be able to do something was Uncle Fred. It was a filthy foggy evening and he was in a filthier temper when I called at Mount Street. The only chance of seeing him was after eight as he always played bridge at the Club till the last moment before dressing time, and then rushed off to take "Auntie" Fullerton to dinner.

p. 142

It was no use my humbugging. "He doesn't know he is," I said. "Richard's a mug. He's got no idea that stuff's dope."

He talked it over and we both came to the conclusion some woman in Paris had put you on to it. It wasn't for some time after that I knew of your affair with Susie. I'd known her with him at his flat in the Rond Point from the first and I knew you went there a good deal though you always were dark about everything that hit you hard. She was just the kind to dope and of course the poor little thing died of it.

Herbert Thal's mistress was in love with you; whether you were with her I don't know and it doesn't affect the result.

p. 147

I didn't care if I never saw the old swine again, but it was a serious matter to quarrel with him. I'd reached a point where thousands would soon be needed to save me from an everlasting smash. I could tide it over a while longer, but if you went down, there was only that vindictive old money-grubber between me and the deluge. As I went down the stairs, I was asking myself whether he would let me go when it came to it; I still had a card that might save the trick. That card was the boy. Whatever I did, I'd always made it a point with Nancy that she should keep on good terms with the governor who thought a lot of her and adored the children. That would have been enough of itself to make the other follow suit. But in addition, since the old man's death, I'd seen to it that Nancy kept it up with Uncle Fred and she took the kids to see him regularly, besides having him to dinner quite often at Northumberland Place, on which occasions I had made a show of being a respectable <pater familias>. I'd also pretended not to notice, and given her strict injunctions to gnore, his little peculiarities. My policy had resulted in his forming the habit of her and the children as I expected he would. In his case habit was a substitute for affection which I always told you he was incapable of feeling. The children, especially the boy, had taken a place in his life, and it was fairly sure that they entered into all his calculations. Someone would have to inherit the millions he was piling up and it would be in keeping with his ideas to tie them up as long as possible. When one considered that the boy was his beloved brother's grandson and the only one of our name in that generation and that under the governior's will he inherited the residue of his estate, what more likely than that old Uncle Fred would let his accumulation follow the lead given by the only human being he had ever been capable of caring for?

p. 155

You said it had come to what you called a parting of the ways, that you'd done your best to make money against every instinct and taste you had, against what you believed were your own interests, but you'd failed and there was an end of it. You'd never try again and she knew now that you'd had enough of that sort of life. Uncle Fred had given you an assurance that if anything happened to you, he'd give her an adequate annuity and she'd have to put up with that and what youcould leave her. The villa and his contents were worth a good bit and your life was insured for a substantial amount.

p. 158

I don't think I saw you again before you went, about a week later. I got a postcard from you from Vienna and one from Constantinople...

...By the time you were in Cairo, I was in Monte Carlo and a couple of months later you were in Paris.

I had a few lines from you from Naples and wired you to come...

.. When first I saw you I thought you looked fitter than you'd been for years; you'd done a lot of riding in the desert while you were at Luxorand the brown hadn't worn off... You'd seen and done all there was to see and do at Vienna, Pesth, Constantinople and in Egypt... You'd kep a sort of journal of your experiences in two big copy-books which you seemed to consider very important documents... After a couple of days you said you'd go back to Naples where you'd felt better than anywhere else...

[The Times, 14/12/1910

An Extravagant Debtor.

The public examination of Mr. Ernest Frederick Wilton Schiff, stockbroker, of Gloucester-place, Portman-square, W., against whose estate a receiving order was made on October 6th, took place yesterday. The statement of the debtor's affairs showed gross liabilities amounting to £48,168 2s. 2d, of which £47,308 2s. 2d. was expected to rank, against assets valued at £40. At the first meeting of creditors, held recently, a resolution was passed accepting the debtor's proposal to pay a composition of 8s. in the pound on his unsecured liabilities.

In answer to the OFFICIAL RECEIVER the debtor stated that before 1899 he lived on an allowance received from his father. In that year he joined in partnership with Mr. H.S. Mosenthal and Mr. L. Samuelson, and carried on business as jobbers on the Stock Exchange under the style of Mosenthal, Samuelson, and Co. In 1906 Mr Mosenthal retired and a new partnership deed was entered into by Mr. Sauelson and himself. He then provided a sum of £20,000 as capital,which was lent by his uncle at 5 per cent interest. He took a one-third share of the profits of the new firm, which traded under the style of Samuelson, Schiff, and Co., at 3, Copthall-buildings, E. C. His share of the profits varied from £4,000 to £8,000 a year.

At the end of 1909 he went for a holiday to the South of France, accompanied by a lady. He bought considerable quantities of jewelry at Nice and Monte Carlo, which he presented to his companion. One of those purchases consisted of a diamond ornament, for which he gave his acceptance for £5,560, and another comprised two strings of pearls and some rings and brooches, for which he gave his acceptance for £6,500. Neither of these acceptanceshad been met, and the jewellers were returned in his statement of affairs as creditors. The holiday lasted about six or eight weeks, and cost him £19,000, including the price of the jewelry. He was well known to the jewellers, who were quite content to take his acceptances. On his return to England he explained his position to his partner, Mr. Samuelson, and in March last the partnership was dissolved. The balance standing to the credit of his capital account was £5,080, which amount he paid over to his uncle on account of the £20,000 lent by him. In addition to his share of the profits of the firm he had received £3,000 a year under his father's will, in respect of an interest which was forfeitable in certain events, including bankruptcy. He was still receiving that sum under the discretionary power of trustees. In May last he went to South Africa, partly with a view to business, but mainly for the trip. Before leaving he consulted his uncle as to his position, and the latter took assignments of some of his debts. His uncle also made payments to creditors, and now appeared in his statement of affairs as a creditor for a large amount. He executed in favour of his uncle a bill of sale, as security, over the furniture at his (the debtor's) house in Gloucester-place, which was valued at £4,000. In consideration of receiving this bill of sale his uncle was to make further advances by way of payments to creditors. He only remained in South Africa for one day, and on his return two petitions were put on file against him by moneylenders, alleging as an act of bankruptcy the execution of the bill of sale. He opposed the petitions and they were dismissed, but subsequently these proceedings ensued on the petition of a Mr. Barnett, who claimed commission for introductions to moneylenders. He attributed his failure entirely to extravagance and the expenses of the trip to the South of France. He had for some time been living beyond his means his income having been about £8,000 a year and his expenditure for the last four years at the rate of £10,000 a year. The money required to pay the composition of 8s in the pound was being provided by his uncle.]

p. 162

What happened when you got to London I don't know. It couldn't have been more than two or three weeks later that I got a letter from you telling me that Elinor had started divorce proceedings and that you were going to marry Myrtle.

[Marion started divorce proceedings in 1910.]

p. 164

I stayed the night at Folkestone and we three had a long talk but on my way up to town I realised that it had been nearly all about your and my affairs and that I didn't know her any the better for it. I liked old Mr. Vendramin and his autocratic ways. He reminded me of mother in the way he walked about as though he owned the hotel and behaved as though it was everybody's business to make things easy and comforatble for him.How I laughed over the two fowls he had sent to the hotel daily from Brighton. Why Brighton? I knew the name Vendramin. hey were a numerous and well-known family. One was at Eton with me, one was on the Stock Exchange and another kept some race-horses.

[Myrtle was Violet Zillah Beddington, daughter of the wealthy Yorkshire wool merchant Beddington. His family surname was originally Moses.]

p. 167

The only member of the family you saw regularly was Uncle Fred. You and Myrtle always went to see him on Sundays and now and then I met you there. Myrtle hit it off with him in an extraordinary way.

p. 168

A man in the City who had something to do with the Income Tax told him Frederick Kurt was worth three millions.

p. 169

About the time you came back from your honeymoon in Venice, The Rock founded and endowed The Kurt Home for Incurables to the tune of a hundred and fifty thousand of the best. I knew where that had come from. It was a part and only a small one of that, of about as bare-faced a bit of robbery as even he ever pulled off...

[The Schiff Home of Recovery was founded in 1908 at Cobham Surrey.]

p. 171

Every now and then there would be a note in the paper about the well-known millionaire philanthropist Mr. Frederick Kurt and his Home for Incurables or there would be a snapshot of him at Newmarket or Sandown. I always made a point of cutting them out and sending them to him. And I worked the ladies...

p. 176

You remember, after he failed for the Navy, we talked over what public school he ought to goto. You were against all English public schools and wanted me to send him to France and Germany...

p. 177

The only thing I knew you did regularly was to attend the meetings of the Committee of the Kurt Home for Incurables of which The Rock had made you and Leslie members.

p. 178

Meanwhile you had bought the lease of a house in Barrington Square and had it decorated in a peculiar manner of your own which you considered modern..

I took a fancy to one or two of them, especially to Barry, that Irish painter who killed himself afterwards, poor devil.

p. 184

Though, outwardly, I was living under the same roof as Nancy when she was in London, actually, I was hardly ever with her.

p. 186

He was growing into a splendid youngster, there was hardly a trace of the Kurts in him. Instead of those dark, beady eyes, he had large blue ones, bluest of blue, with long dark lashes and a nose that tilted up instead of down.

At that time I'd almost given up on the Stock Exchange.

p. 187

From every side I heard of his growing wealth and the enormous scale of his deals. He was in syndicates with all the big bugs and had interests in every part of the world. You came back from Switzerland about the same time as we did from Dinard and one of the first things I told you was that he would soon be getting a knighthood or a baronetcy. You laughed at me, but a few weeks later he got his K. C. V. O.

[He was knighted in 1911.]

p. 188

With all his money he never enjoyed himself. He didn't know one of his horses from another and whenever he went racing, he was only thinking about his book. He never knew how to spend monet, even to be comfortable. He had that huge flat and lived in one room of it; the place never looked lived in. He bought old pictures and antique snuff-boxes and miniatures, but as his one idea was to pick up bargains and to buy cheap, most of them were stumers.

p. 189

I met Stanford at your house.He was a gentle creature and I thought, through him, I could get to know something about pictures.

...He told me you had dropped him and taken up with what he called 'Futurists'...

p. 192

You had taken a house on the Wye for the summer. Eugene Hartmann was staying with you and you wrote me that he was very pessimistic about the European situation.He was one of the few old friends of your Elinor days you'd stuck to. I knew he was adiplomat and well informed, but I wasn't in the mood to bother about politics and I hardly looked at the papers. The morning in bed was my usualtime for reading them and the boyhad abolished that by making me go for a swim early and come back to a huge breakfast out of doors. My ignorance didn't last long. A week later, was was declared and I knew Frenchmen well enough to get home sharp.

p. 197

..."When there's a megalomaniac on the throne like the Kaiser---"

He turned the paper over and without looking up, threw at me, "You know nothing about it. You only repeat the rubbish that you read in the yellow press."

p. 199

You stayed in the country till the end of September partly because old Mr. Vendramin had recently died and you had Myrtle's mother staying with yo. I had got my commission. You were just as much carried off your feet as anyone at first. You joined the League of Frontiersmen while you were away and though you didn't tell me, I heard you'd been to the O. C. of your old Yeomanry and that he'd turned you down because you were over age.

p. 200

...He said little or nothing to anybody, just went to the City every day and from there to the Bentinck to play bridge as he always did. Those were the early days when everyone was repeating that story about thousands of Russians passing through England in trains with th blinds drawn, on their way to surprise the Germans. I had been told the story circumstantially so many times that I fully believed it and when Leslie told me that The Rock was beginning to make himself unpopular at the Club by throwing cold water on the whole thing, it seemed to me typical of his obstinate disbelief in everybody.

Another item of newsfrom Leslie about him was when Sir Edward Field, the K. C. who defended all the big criminals and was supposed to know as much as anyone at the Bentinck about what was going to happen, said that the war couldn't last more than six months because the Germans wouldn't be able to find the money. The Rock took him up in front of the whole room by remarking that lack of money had never stopped a war yet and never would, and that evidently Sir Edward Field knew very little about the might of the German Empire. That didn't increase his popularity.

[Sir Edward Marshall-Hall KC]

p. 201

I thanked my star he was only just fifteen and well out of it. At the worst, the war couldn't last long enough to mop him up... He kept up a desultory correspondence with Myrtle's twin nephews who were at Charterhouse.

[Beddington-Behrens]

p. 206

...But the casualties kept increasing, more and more of one's friends' sons were among them. Myrtle had a large number of relations in the Army and several had been killed or wounded. Her brother's elder son was at the front, the younger one would soon be going. Our cousin Jack had got his commission in the Scots Guards. The war was getting nearer.

The boy got his cricket colours that summer and he was the youngest in the eleven. You and I went down to see him play against Charterhouse and the twins got leave and came too.

[He was a fairly good bat and useful change bowler. (Wisden)]

p. 207

By the early winter the twins were gazetted to their regiments. Both were in the R. F. A. but in different batteries. Walter was in the North of England somewhere and Francis on Salisbury Plain.

p. 211

And what riled me more than anything was that you were standing in with that old swine The Rock, who was a notorious pro-German. Everybody made remarks about it.If it had been only what Leslie said, I might have ignored it but I heard the same thing right and left, and what I chiefly minded was the effect it might have upon Cyril's career in the Army. And when I spoke to you seriously about that, you jeered at me. You denied Uncle Fred was pro-German...

...All the same I was sick with you and I got sicker still when there was that row at the Bentinck. He still went there every afternoon to play bridge and it says a great deal for the members that they stood him so long. But when it came to his defending the torpedoing of the Lusitania, it was a bit too much and he had to resign. You said he didn't defend the sinking of the ship. As you weren't there, I don't see how you could know anything about it. What he said was "They were warned." If that wasn't defending it, I don't know what was. After he had to leave the Bentinck, he took to going to the Cobden again for a time. He was one of the original members there and had subscribed to keep the Club going when it was in low water so they had to stand him for a time, but it didn't last long. I took care of that.

p. 213

That winter, air-raiding began proper... meanwhile poor Jack got killed and it put it out of my head. Nancy had always kept in with the Theo family and had been especially thick with them since the war, so the boy had got fond of Jack and was awfully cut up.At the same time The Rock had one of his periodical attacks which sent him to bed.

He still went to dine at Olivia's, but less often. I think this was partly because some of Leslie's gossip had reached his ears. The Rock had his knife well into him one evening when I was of the party and I had a notion that a row wasn't far off. A short time afterwards it came. Olivia telephoned to me: she was dreadfully upset about it. The old man had been dining there the previous night. It so happened that Leslie had heard that afternoon that the Committee of the Cobden had posted a notice that members having any German or Austrian relatives or connections were requested not to feequent the Club, and that The Rock, regarding this as a personal insult, had sent in his resignation...

...Leslie, stupid as always, thinking the day had come when such an old pro-German would take anything lying down, let off something so blatantly offensive that The Rock got up from the table, kissed Olivia good night and walked out of the house, without another word.

p. 217

The day Cyril was gazetted to his batallion, you got the telegram about poor little Walter.

p. 224

...You were right when you said, if it had to come, it was best it come quickly. Think of it. One short month, no, one fearfully long month, the longest ever lived from the day I saw him into the train at Victoria to the day I got the telegram, the fourth day he was in the firing line, the first time he went over the top. Thank God he was shot dead, that's my one comfort, and only one bullet; he wasn't even disfigured. As he was at Victoria, head and shoulders out of the window of the train, stretching out his hand for me to hold one second more while I looked for the last time into his dancing blue eyes, so he was when he fell. There's nothing more to say; it was the end of everything for me and I knew it.

[On the 9th April, the only son of Mr. and Mrs. E. Wilton Schiff was killed in action. He was 2nd Lieut. Alfred Sydney Borlase Schiff, of the Rifle Brigade, and his age was 19 years.]

Lieutenant, Rifle Brigade

Born: November 27th 1897

Died: April 9th 1917

Age at Death: 19

Killed in action, France, April 9th 1917

R.M.C. Sandhurst Rifle Brigade (Second Lieutenant 1916)

Son of Ernest Wilton Schiff.

Obituary Brightonian XV April, 1917

Schiff entered the School House in May, 1912. He distinguished himself as a cricketer at the College, getting his Junior XI. colours in 1912, Second XI. in 1914, and First XI. in 1915. The following extract from a letter of a senior officer will interest all O.B.'s who knew him:- "It will be a great comfort to know what a splendidly gallant end his was. Our objective on Monday was - Redoubt, some 6,000 yards behind the German lines. We had been practising for the attack ever since he joined us, and he was keener than any one. We soon knew the order of battle and my Company was leading. We attacked on a two platoon front - his platoon was on the right and directed the whole battalion in the attack. Ours was the furthermost objective on the first day. We had seen aeroplane photos of the Redoubt. There was a trench leading east away from the Redoubt towards the Germans. We were always talking about the attack of course, discussing what to do and all about it. Your son's job was to go straight across the Redoubt, consolidate strong points on the other side and put up a barricade in this trench. He was always talking about this barricade, and what a jolly good one he was going to make. The right hand corner of this triangular Redoubt was called 'Schiff's Corner', this being the corner which would probably be reached first and which his platoon would go over. He had the map reference on the back of his identity disc. On Monday, the battalion started from camp about 6.20 a.m., and marched to their first assembly position. Our attack did not start until 3 in the afternoon. The battalion went through the objectives gained by other divisions. The attack went off just as we had practised it - No.11 platoon leading and directing. They kicked their football right into the Redoubt, advanced over it and started consolidating. He made his barricade. One of his Lewis gunners was firing at some retreating Germans, but that was not enough for him. He seized the Lewis gun and started firing it himself, when he was shot through the heart by a German sniper. It must have been quite instantaneous. He died having done his job and done it splendidly, and you can well be proud of him. He is a very great loss to the battalion, and the company won't be the same without him. He was always so immensely cheery and keen and we were all so fond of him. All his men loved him, and on the night before the attack, when I was going round wishing them all good luck, many of them told me that they would follow him anywhere."

p. 225

...They were all very kind. They were kind when Jack was killed and Walter, and now they were being very kind about Cyril. I stayed on with Trixie at Margate for a day or two and then we went back to Dante Gardens.

...The Rock called upon Nancy regularly; she had taken rooms at a private hotel, and it was there that I saw him first after the boy had been killed. He was looking whiter and older and, though he didn't complain, there was no doubt that his frequent attacks were weakening him.

p. 227

Then I got bronchitis and you came to see me... I had lost my son and I was ill, so he came to see me.

p. 228

The Rock was spending the summer with Aunt Kate in the Isle of Wight and news reached me through Nancy that he was failing fast. My one thought was, what position should I find myself in when he died? Then you heard from Olivia that he was back at Mount Street and you went up to see him. He told you he thought he could see the end of the war, that was what he was living for; to see his sisters once more and to make them comfortable for life...

He lasted throughout the early autumn. The doctors told us he couldn't live more than a few weeks, but he didn't give in. They kept him alive with morphia, and he got up and dressed. He couldn't go to the City but he gave his orders over the telephone and Kahn and Bellows came to make their report morning and evening. Only at the very last, his mind wandered and he spoke constantly about his will, telling everyone a different story about it. He died on the eighth of November. On the eleventh the guns were firing salvos to announce the Armistice as The Rock's coffin was being lowered into the grave, beside that of the only human being he ever truly loved, his brother's. And the eleventh of November was the governor's birthday.

p. 230

After all, the old man treated me fairly. His fortune was about a third of what it would have been but for the war and of that he bequeathed a tenth to charity, but there was enough for everyone to get a decent share. Mine, as you know, enabled me to pay my debt to the Bank and left a nice little surplus in hard cash.

For some time before The Rock's death, in fact not long after the boy was killed, I had been thinking of getting Nancy to divorce me. We had been nothing to each other for years if we ever were. It took her a long time to discover my infidelities but, once she did, whatever the feeling might be called for me died a natural and painless death.

p. 231

Some time before I had commissioned Stanford to do a posthumous portrait of Cyril from photographs...

It was Stanford's idea to go down to a Cornish village he knew of on the Cornish coast where he could paint the portrait at his ease and I could watch it and make suggestions.That suited Trixie and me all right, our intention being to stay there a few weeks and then go to France until the divorce was a fait accompli.So she chucked her engagement at the Lyric and we went down to Portherrack and took the whole inn.